Seattle needs parks, not just ‘parklets’

Tuesday, June 28, 2016. By Knute Berger.

I admit that my expectations might be way off. I grew up in Seattle in a part of town you might call The People’s Republic of Olmstedia.

The Olmsted Brothers firm shaped modern Seattle into the livable city we know, the city we fear losing bit by bit. Their innovative landscape designs and parks vision are part of our foundational infrastructure. But has it runs its course?

There are certainly indications that the city’s interest in maintaining that vision is at risk.

My childhood home and my father’s childhood home were located along Mount Baker Boulevard as it snakes from McClellan to Rainier Avenue. It features a chain of open boulevard parks; when I was young, it even featured a few ornamental rose gardens. You could play under broadleaf trees, yet have enough open space for neighborhood football or tag. Within walking distance is Lake Washington Boulevard, Colman Park, and the long shoreline boulevard that runs from Seward Park in the south to Montlake in the north.

In many cases these parks are better today than they were half a century ago, improved with more exciting playgrounds, native plants have been restored, trees and foliage that have matured. A pond in Mount Baker Park once was a fetid, mud and slime-choked mess. Now it runs clear. There are even goldfish there, not native, but pretty.

The neat thing in my youth was that you didn’t have to be rich to have access to these treasures. They were designed by the Olmsteds as part of Seattle’s attempt to create an amazing park and boulevard system for a burgeoning urban population.

And it worked. In the depths of the Boeing recession in the late 1960s and early ’70s, whites fled to the suburbs, and pockets of poverty in the Rainier Valley were persistent, even the humblest Seattleite had free and easy access to these green spaces. I took that for granted: Surely, everyone in Seattle had parks like these. It wasn’t true, but it was more true here than in many other cities.

Walking recently in Mount Baker and Colman parks, I was struck by how durable and beautiful this legacy is, and the quality of the original craftsmanship. The park designers argued to preserve old growth and limit cars. They built park restrooms to look like sturdy English cottages. Now, in some parks you’re lucky to get a Honey Bucket.

In Colman Park next to the Mount Baker bathing beach, the Parks Department has a sign that quotes Frederick Law Olmsted, the patriarch of the design firm that shaped our city. His philosophy was to create “ground to which people may easily go after their day’s work is done, and where they may stroll for an hour seeing, hearing and feeling nothing of the bustle and jar of the streets.” The commitment to this vision is one of the things that has made Seattle special, and we still love our parks. We have vast volunteer networks, green space restorers, millionaire donors and foundations to help take care and enhance them. But can we remain committed to extending these great benefits to the larger population in the denser, bigger city we’re building?

I worry about whether we’ll continue to create parks that share these commitments. InvestigateWest did a story recently about the city potentially slipping away from its commitment to expanding parks — real parks — in the new draft of the Comprehensive Plan.

There’s a commitment in the plan to “open space” in a rapidly growing city with real-estate values skyrocketing, but this increasingly means painted intersections — “pavement parks,” or “parklets” that turn curbside parking spaces into pedestrian oases. These painted streets and jerry-rigged curb spaces, where chairs and tables are placed to form little plazas, are a great idea. But they are no more parks than are traffic circles, and certainly they don’t meet the original Olmsted standards.

Our Sponsors

Will Seattle dial back its park ambitions due to growth pressures, and decide mostly to make do? Old-school parks are deemed too expensive — unless it’s the proposed new waterfront extravaganza, billed as a “park for all” but actually a corridor that will serve transportation, downtown residents and tourists. Fine, but not enough.

The city had to bite the bullet and acquire property during previous building booms — and in this unprecedented one, the space won’t come cheap. But that isn’t stopping us from pushing for major investments in the tens of billions for light rail and more public housing. At the same time, the city is considering selling off a major parcel of potential park property in Southwest Seattle. Surely opportunities like this are rarer than the chance to build affordable housing throughout the city.

Parks in underserved areas are essential.

Thinking big, I would love to see Seattle’s 19th century bike boulevard system rebuilt with dedicated, green bikeways throughout the city connecting the old boulevards and creating new ones. This might mean using existing street right-of- ways and alleys very differently, perhaps eliminating cars from some existing boulevards.

We could also do better by redeveloping many of the waterfront street ends and improving access to them — many are mini-parks waiting to happen. A plaza atop the U-District light rail station was proposed and rejected, but that is the kind of opportunity that should not be missed in neighborhoods that will be dramatically transformed in the years ahead.

We should consider repurposing some of our older parks. Back at the beginning of the 20th century, public land atop Beacon Hill was in play — one plan was to build a cemetery there. The citizens of South Seattle pleaded with the city to build a park, saying that their end of town was being chronically shortchanged compared with the north (some things never change). The city cleared the land and built Jefferson Park with prison labor. But what did they build? A golf course! The elite users won out over the people. Such things happen — for a while, the land that is now the Arboretum was claimed by wealthy folks who wanted it reserved for harness racing and an equestrian center. Fortunately, that failed and it was transformed into what we have today, and which is currently being improved with new trails. If the city cannot find new Jefferson Park-like parcels, could we consider remaking the park for wider use?

There are also park-like repurposing opportunities at Seattle Center. The Center did not grow out of the Olmsted ideal — it was a love child between Disneyland, Rockefeller Center, Century 21 and Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens. And while it must remain multi-purpose, green space could be dramatically expanded if the city could acquire Memorial Stadium from the Seattle School District. That site offers a tremendous opportunity, especially in light of the failure of voters to back South Lake Union’s Commons project.

Another concern is the values of Seattleites themselves. We’ve been known as tree-huggers, but too many people now are tree-butchers. This spring’s debacle of clear-cutting a public hillside in West Seattle is the poster-child of the phenomenon. Yes, our pioneers cut trees, but over the course of the 20th century, we became a city that saw the value of green canopy, beautification, hillside stabilization, wetland preservation, salmon and native species restoration, and habitat for critters. The ethic of green preservation is widespread in Seattle, but there are too many people who think too selfishly. We need tougher penalties and enforcement. Maybe we need Olmsted re-education camps!

The sense of shared commitment needs to be reinforced. Despite growth, cheap and quick is not the only answer. Parks citywide should be created, some reinvented and improved. We need to build with an ethic of permanence and expansion. Seattle’s open space cannot be protected and parks cannot be created by buckets of paint and folding chairs alone.

No room for trees in Seattle’s new parks

Wednesday, April 27, 2016. By Mark Hinshaw.

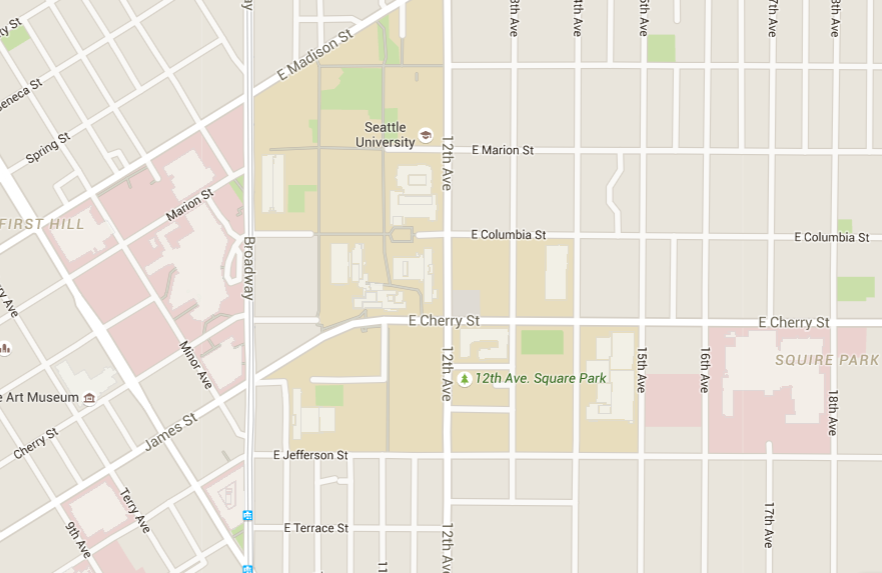

Ellen Sollod’s “Cloud Veil” at 12th Avenue Square Park. Credit: Seattle Parks & Recreation Credit: Alex Garland

Forget what you think you know about green Seattle parks. A new park just south of Seattle University shows us an important aspect of the future in a more densely developed city.

The recently opened 12th Avenue Square Park is the sort of open space we will likely see more often. It is more like a piazza, surrounded by development — both older and newer, with more buildings to come.

Seattle has a long tradition of building fine parks. The early 20th century’s Olmsted Brothers plan gave us long sinuous greenbelts following topography and shorelines, and great swaths of mature trees that seem to weave the Cascadia forest right into the middle of the city. The closure of two expansive military bases gave us two magnificent natural parks adjacent to water, Discovery and Magnuson. The Port of Seattle has added more public spaces. Former landfills and industrial sites along waterways have been converted to usable open space. And Seattle voters have for decades consistently approved tax increases to fund more parks.

Yet reports by the city indicate that some parts of Seattle continue to have open space deficits. Dealing with those will require different approaches, including putting smaller parks in the heart of neighborhoods where more people are living.

We in the Pacific Northwest value large verdant open spaces with a pristine, pastoral character. We like doing stuff outdoors, whether it is hiking, biking, boating, skiing, or just plain old strolling. We are lucky to live in a part of the world where in some months, you can do all of the above within a short distance away.

Credit: Seattle Parks & Recreation

But 12th Avenue Square is a new kind of open space that we are beginning to appreciate — one not necessarily defined by flora and fauna, topography or hydrology. We also want spaces that are active, energized, filled with people and may include expressions of art.

This type of space often involves no vegetation at all, but rather sets up a literal stage where people and performances change all the time. In a sense, we are finally learning to emulate the lively urban spaces in European cities.

For Seattle, this has not come without some painful lessons. In the past we built natural parks and pretty much stopped there. That is simply not possible with urban parks which have more to do with human behavior and economics than natural resources. Indeed, urban parks require two things to keep them successful — frequent maintenance and on-going programming.

We learned this lesson with both Westlake Park and Occidental Square. Over the years, both places were becoming social cesspools of drug use and dealing, aggressive panhandling and daytime encampments. Fewer and fewer people felt comfortable using them. They were places you quickly passed through rather than lingered in.

In the last year, however, mostly due to the contributions of companies and civic organizations, both places have been completely transformed. Tables and chairs are set out in the morning, and food trucks attract people from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. People play ping-pong, take yoga classes, shop in occasional tent markets, and listen to music. Changing art is part of the picture. There are still people from the complete spectrum, including the homeless. But both public spaces are immensely more usable and welcoming.

The best part is that you can now see young children using these spaces, as more families with children live downtown.

The new 12th Avenue Square Park seems designed to work well from the start. As with many classic urban spaces, this is about horizontal surfaces. European spaces often provide a floor that is rich in texture and loaded with spots to sit, whether its ledges, steps, benches or portable chairs. The 12th Avenue space has a floor with a swirling design and disks that pop up to sit on.

It also has a second horizontal element, a circular ring of steel that is suspended by slender cables, forming a kind of ceiling. Designed by artist Ellen Sollod, this element offers much more than the often-seen string of lights, which designers can specific from a catalog without much more effort than clicking a mouse.

Sollod’s piece is, well, solid. Entitled Cloud Veil, the piece visually defies gravity by placing an arrestingly heavy object directly over our heads. It marks the place and contains it – Attention s’il vous plait! The shallow polished bowl shapes hovering inside the ring pick up ambient light and reflect it back, as if they were lighted themselves. The feeling is not unlike the scene in Close Encounters when the mothership descends close to the ground.

There is something special here. This is a place that is especially enjoyable at night.

Hewitt Architects was the overall designer but the close architect/artist collaboration is evident. This is not a case where the artist comes in later with a “site-specific piece.” Here the site design and the art are fused together. Its hard to tell where one stops and other begins. Moreover, the space is simple, coherent and bold. (Lately there has been a tendency to load public spaces like baked potatoes, piling on such toppings as lights on sticks, bricks for paving, and benches without backs. These are the bacon bits, grated cheese, and chives of urban design.)

Hewitt also designed an elegant “woonerf” — a slow-moving, quiet, narrowed street that allows for walking and biking — next to the square. Unlike Bell Street, in which a Belltown street was forced to be a park, this design provides a safe, serene, car-free space next to a transportation corridor. Everyone is accommodated without signs futilely trying to alter the errant and entitled behavior of drivers.

The 12th Avenue park offers a prototype for future urban parks that we will need as we become more dense as a city. It is compact and doesn’t require buying a lot of costly land. It has “eyes” on it from the adjacent businesses and apartments. It is open and accessible and can easily accommodate neighborhood scale events and programs. Best of all, it is magical: It makes you gaze with wonder. It doesn’t get much better than that.

The park sits on a plot of land barely bigger than a single-family house lot. At a little over 7,000 square feet, its tiny by comparison to most other parks. But its value socially as a dramatic town square for the Squire Park neighborhood is enormous. That neighborhood — one of the least well-known in Seattle but a rather distinctive part spot overlapping part of Capitol Hill and the Central District — has long needed a sense of center.

This park definitely gives it one. And it provides a model of what can work in other neighborhoods as we continue to become a more mature, diverse, and dense city.

As Development Booms, Seattle Gives Up On Green Space

By Adiel Kaplan.

So-called pavement parks are a growing trend in major American cities and they’re one of the new ways Seattle is looking to increase open space without spending billions

From atop a steep slope above Myers Way in West Seattle, Cass Turnbull peers over a tangle of blackberry bushes. Her perch affords her an exceptional view of the distant Cascades. But her gaze fixes instead on the island of undeveloped acreage more than 100 feet below the blackberries.

“My dream for this area is a nature play area,” Turnbull says, noting the wetlands, slopes, forests, fields and creek below. Her vision: “Kids get to interact with nature and explore.”

Instead, this green island — the largest piece of undeveloped ground owned by Seattle taxpayers with the potential to be turned into a decent-sized city park — is up for sale. The city tried this once before, in 2007, but the Great Recession scotched the deal.

“When I found out they were trying to sell it again, I couldn’t believe it,” Turnbull says. “It just rubs me so much a bad way.”

Drivers heading toward downtown from White Center along Myers Way would have a hard time knowing the peril of the leafy lands they pass. But Turnbull and a handful of other green space activists from across Seattle have been battling the city for almost a year to keep this particular green canopy from being transformed into acres of asphalt and concrete. City officials say they need the cash to alleviate the homelessness crisis, a position that infuriates parks activists such as Turnbull, who say the issues are unrelated.

Cass Turnbull has been battling the city for almost a year to keep this green canopy from being transformed into acres of asphalt and concrete.

The issue comes to a head later this year when the City Council makes a final decision about the potential sale. But make no mistake—the debate around the so-called Myers Parcels is just one piece of a much larger issue facing the city. Put simply: We are running out of open space.

“The mayor continues to focus on affordability as a key challenge,” said Murray spokesman Jason Kelly.

Seattle has long touted itself as one of the greenest cities in America, and in fact was named the nation’s most sustainable city. It boasts of numerous parks, green building standards, energy efficiency programs, and a commitment to carbon neutrality, among other attributes. Yet, to Turnbull’s TreePAC activist group, the Seattle Green Spaces Coalition, and the Veteran Conservation Corps, among others, the city doesn’t value parks and green spaces as much as it should. The groups, which have united to push for protection and development of these aspects of the urban environment, cite benefits to tourism, public health, water and air quality, and the flood risk reduction that parks provide.

The first update of the Comprehensive Plan, written in the go-go mid-2000s, sought open spaces that would help make growth sustainable and perhaps even pleasant, setting a goal of one acre of open space for every 100 residents. But after the rapid growth of the last decade, and subsequent rise in property value, city officials say many of the goals from the 2005 plan are no longer achievable

“There simply isn’t that much land available in the city,” says Tom Hauger of the city’s Office of Planning and Community Development.

The new draft of the Comprehensive Plan, released last month and currently being reviewed by the city council with a vote expected sometime this fall, doesn’t include any prescribed measurements. It defers the particulars to next year’s update of the Parks Development Plan. In place of those metrics are broad statements about “realistic” and “attainable” goals and vague plans to look for “new strategies that take advantage of limited opportunities” — opportunities that are, yes, decidedly constrained by the city’s current parks-acquisition budget.

The city Budget Office and Parks and Recreation department crunched the numbers last summer and concluded in a memorandum to the City Council that Seattle is growing far too fast to do what was envisioned a decade ago. They reckoned that would require buying 1,400 acres — nearly 20 times the size of Seattle Center and representing a 20 percent increase in the city’s total parkland — over the next two decades. The $20 billion to $30 billion it would take to make that purchase is out of reach, they say, for a city with a general fund that runs just a tad above $1 billion a year.

Not only is the city reluctant to purchase that amount of new land; it is now selling off the Myers Parcels, one of the most valuable pieces of undeveloped ground in its inventory.

Walking through the north end of First Hill, it’s hard to miss the bright blue swath of pavement at the junction of University and Union streets and Boylston Avenue. Until last year, this part of the city was just another underutilized intersection, but since then it has been transformed into what the city calls a “pavement park.” Yep. Nearly devoid of green. And hemmed in on either side by traffic.

On the blue-painted asphalt sits a group of bright pink metal chairs and tables, separated from passing cars by large cement planters. The incongruous setup, with its cheerful color scheme, is the latest in what the city calls “creative” solutions. And it’s one of the first of such parks that may soon dot the cityscape.

Pavement parks are a growing trend in major American cities and they’re one of the new ways Seattle is looking to increase open space without spending billions. The city is turning public rights of way and lightly trafficked intersections into outdoor public spaces.

On a sunny day at the pavement park on First Hill you might see a couple of people eating lunch or checking their phones. It’s definitely a cute improvement on the largely unused intersection that came before. But the bright blue pavement doesn’t look anything like, say, Discovery Park. You know. A real park.

That’s precisely the issue that city residents like Tim Motzer take with it. Motzer, a former parks department employee and current City Neighborhood Council representative, analyzed the new draft Comprehensive Plan and found that the city was “basically looking at using streets as a substitute for actual parks.” He acknowledges that buying new parkland is expensive and argues that creative solutions to finding more open space are important—but painting the pavement doesn’t cut it.

In contrast, City Council Member Rob Johnson is excited about the idea of expanding the definition of open space to include these public rights of way.

Park at East Union Street and Boylston in Capitol Hill

“We have in this city about 30 percent of our total city land as roads and streets. And that is a huge opportunity for us to consider creating a lot more open space in the city,” he says. He speaks fondly of plans to create more parks in intersections, semi-permanent parking space “parklets,” and neighborhood “play streets” at certain times of day.

Johnson acknowledges that no one is going to confuse sitting in a parklet with actual green space, but parklets fill a major need in the city by creating the feeling of community in dense areas at low cost, he argues: “We need to have green space, but open space and community gathering space are just as important.”

Consider that about the same time the Comprehensive Plan went into effect two decades ago, Seattleites had the opportunity to create a huge patch of green space — but blew it, parks advocates say.

The so-called “Seattle Commons” was to be 61 acres of parkland stretching from downtown to Lake Union, what Historylink.org called a “vast civic lawn framed by high-tech laboratories, condos, restaurants, and urban amenities.”

Voters said no. Instead it stayed underutilized industrial land for another decade-plus until the current Amazon-anchored building boom there ensued. Today a city-produced map showing gaps in open space reveals big swaths of South Lake Union underserved by parks. The same goes for many other neighborhoods, including Sodo, downtown, Fremont, Bitter Lake, Northgate, the U District, Ballard, First Hill and Capitol Hill, all areas that make the neighborhood around the Myers Parcels seem relatively well-served.

Voters did show up for parks in 2014, when they approved the establishment of a Seattle Parks District, run by the city council, and an accompanying levy that supports a $48 million annual budget. But only $2 million per year of that money has been budgeted for acquisitions in the face of the minimum $2 billion a year the city would need to spend to keep up with the current goal.

That money isn’t even targeted for buying big parks like the Myers Parcels; rather, it is supposed to go toward improving walkability to parks in the city’s densely populated urban villages, such as Ballard and First Hill. Even that seems like a too-tall order. At the price of property in Seattle today, $2 million would buy about 5,000 square feet in First Hill, according to Parks and Recreation Acquisition Planner Chip Nevins. That’s roughly the size of two large houses.

Then there is the fact that the city currently faces a $267 million parks maintenance backlog. Mayor Ed Murray campaigned on a promise of closing that gap, boosting maintenance and development of existing city parks.

This emphasis on existing parks first has environmentalists worried. They fear that if the city doesn’t acquire new green spaces now, there won’t be any new green space within the city to acquire in the future, or what will still exist will be prohibitively expensive.

Seattle has added nearly 90,000 people over the last ten years, and an additional 120,000 are expected to move to the city over the next twenty.

Amid the push for density to house those people, is the city properly valuing its parks and open space? Perhaps not, judging from a 2011 study on the economic value of Seattle’s parks by the Trust for Public Land. The report points out that the parks system provides direct monetary benefit to the city and the private sector. Toting up the value of parks to tourism, public health, water and air quality, and flood risk reduction, among other areas, the report estimated savings to the city government at nearly $32 million a year. One-tenth of that is savings in controlling water and air pollution — value that cannot be acquired through pavement parks. City residents reap most of the parks’ value: $511 million a year in exercise, health and similar benefits, and $110 million in higher property values and tourism-related earnings.

More than five years after release of that study, Seattle still is figuring out how to translate those numbers into city policy. Last November the City Council directed city departments to start incorporating the value of green infrastructure into the city’s asset portfolio. It’s a slow process, though, and won’t be far enough along to have any sway over the policies of the Comprehensive Plan before it’s passed by City Council this fall.

Council Member Johnson, who is chair of the committee in charge of the Comprehensive Plan, which has scheduled its first public hearing on Monday, June 27, at 6 p.m., noted that this update to the plan is not as strong on environmental goals as previous versions.

“As we as a council work our way through the plan, that’s a value I want to make sure we’re not losing,” he said, adding that “whether it’s transportation, land use, or open space, those things all are critically important in our goals of carbon neutrality and sustainability.”

Despite those sentiments, back at the Myers Parcels, the city has found financial temptation to be too strong. The growth explosion of the last decade that drove real estate prices skyward had the same effect there, boosting its 2003 value of $2.5 million to $14 million today.

Ruben Deleon grew up in a house that bordered the Myers Parcels. He recalls many afternoons spent exploring the undeveloped lot with other neighborhood kids.

“It was really my first exposure to being outdoors,” he says, listing different animals he saw there — hawks, moles, goats, even coyotes. Now 23 and a University of Washington student, Deleon no longer plays in the Myers Parcels. But he, like Cass Turnbull, would like to see his old stomping ground become a public space for future generations rather than asphalt and concrete.

“I’m studying construction management,” he says, chuckling. “You’d think it’s something a student studying that would want, but I think we do need the open space.”

The parcels aren’t just a nice patch of green; they’re also a natural buffer for the neighborhood against nearby industry. To the east, the industrial parts of West Seattle and the Duwamish River Valley sprawl out. On the northern edge lies the city’s Joint Training Facility for city firefighters and utilities inspectors. And to the west, King County intends to build affordable housing.

Despite all the nearby industry and the busy traffic of Myers Way, just a hundred feet inside the property, the sound of cars fades away, replaced by the calls of birds and the rustle of animals in the undergrowth. Walking around, you can almost forget you’re in the city as the trees close you off from all but a view of the top of the training facility next door.

The city acquired the property from Nintendo in 2003, looking to build the Joint Training Facility. Nintendo refused to sell just a portion of the property, so the city took a loan to pay for all of it, ending up with more than 30 acres of additional land. The city’s Facilities and Administrative Services department took control of the excess property and asked if other city departments were interested in the land. None were. So it went up for sale. The city then entered into a contract to sell the land to Lowe’s, but Lowe’s backed out and the recession hit and the sale was put on the back burner.

Fast forward to 2016 and the city has started the same process again.

Despite local residents’ push for a park or affordable housing, neither the city housing office nor the parks department wants the land. The housing office says since the site was once a gravel mine, about a century ago, it’s not a good site to build, especially with the added cost of extending sewers and electric lines to the property. The parks department objected as well, preferring to use its budget for that part of town to maintain and improve Westcrest Park, less than a quarter-mile away.

It’s not a city priority to keep it because by the city’s density-based standards there is already enough green space in that area. And even if another city department wanted to take over the land, it would have to pay off the remainder of the loans.

Murray isn’t having any of that. “The mayor continues to focus on affordability as a key challenge,” said Murray spokesman Jason Kelly. The current plan would reserve five acres to expand the Joint Training Facility; sell off the largest part of flat land, about 13 acres, for commercial development; and keep the remaining southern and eastern sections of the parcels as open space for now. Those two sections totaling 22 to 24 acres have the most tree coverage but are divided by busy Myers Way, and contain steep slopes and wetlands, limiting accessibility to pedestrians and making them unlikely candidates for parks.

The city is also looking for a buyer for those last 22 to 24 acres, with the stipulation that the buyer would have to preserve the natural environment of the property. If no buyer is found in the next two years, the land would be folded into the parks department holdings.

The plan to sell the developable 13 acres still has to be approved by the council this fall. The parts slated for development include federally protected wetlands that would have to be built around, a task the city failed at when constructing the Joint Training Facility from 2004 to 2007 (only to be caught by environmentalist John Beale. The city paid $4 million required by federal authorities for environmental enhancements in the area to make up for the damage. Later the city agreed with environmentalists to pay for an additional $400,000 worth of work, but that has yet to happen).

The 13 acres for commercial development are expected to sell for $10 million to 12 million, $5 million of which is to be used to help the homeless, keeping with a plan that Murray announced in November and for which the council soon after earmarked funds. Another $1.3 million would finish paying off the original loan, and $500,000 goes for city contractors and expenses. It is unclear where the remaining $4 million to $6 million would be spent.

Parks advocates say if the city goes through with the deal, it will be sorry. Yes, homelessness needs attention, they say, but Murray is creating a false choice between helping the homeless and green space.

“We can have both,” Turnbull argues.

And as for the Myers land, she said: “There’s a lot of good reasons to keep it, the main one being you’ll never get another piece of land that big.”

A public hearing on the Comprehensive Plan is scheduled at 6 p.m. Monday, June 27, at City Hall. A public meeting on the fate of Myers Parcels is scheduled June 30 at 6:30 p.m. at the Joint Training Facility.

Robert McClure contributed to this report.

Dear Sara Bernard,

I was forwarded the report titled ‘Have Seattle’s Urban Forests Dodged Development’

The true answer is, “No, they haven’t.’

The Seattle parks department is certainly not going to sell off the city’s parks, but City Parks only controls 25% of Seattle’s tree canopy.

By far the largest part of the city’s canopy is located in ‘single family’ zones. They contain 62 % of it. With the building boom not yet underway (between 2001 and 2007) the single family lots undergoing redevelopment lost 41 % of their canopy cover. Multi-family lots undergoing redevelopment lost 69% of their canopy. Buildings, including MacMansions, mother-in-laws, townhouses, apartments, and institutions, are all getting larger. There’s less room for trees to grow. If one looks to the future, one can see that private open space is diminishing faster that public space (street trees and parks) can add trees. The only hope is to ADD more public space. But it is a race we are losing. Roughly half of the Urban Villages don’t meet our own open space goals now. And we have 200,000 more people headed our way.

But the worst is yet to come. Instead of trying harder to meet open space goals (open space or permeable surfaces determine the amount of planting spaces available for trees) the new Seattle Comprehensive Plan is proposing to reduce the open space goals for Urban Villages! The people living in those ironically named villages are people who don’t have back yards to go to with their kids or pets, and they are supposed to be biking or walking on the hot, dirty, crowded streets, not driving with the air-conditioning on. They need more shade and public green space, not less. The national recommended ratio of parks space is 1 acre of public park per every 100 residents. Seattle’s current average, last counted, is about 8.9 acres per 100 residents. But the goal for the new Urban Villages is .5 acres per 1, 000 people. That’s 1,000 people, not 100.

Right now, green space activists are trying to prevent the City of Seattle from selling one of the largest undeveloped tracts of land remaining in the city. It is Myers Parcels, 38 acres of surplus City land made up of wooded, steep slopes, wetlands and open grassy fields. The City already filled in one wetland on the site (oops!) to build a $33 million training facility for the firemen. They say they’ll be careful not to damage the environment when they sell off the rest of it for commercial development. You should do a story on that.

Cass Turnbull

TreePAC

206-783-9093

Data sources. the Urban Tree Canopy Analysis Project Reort 2009, the Mapleleaf Comunity website, the proposed 2015 Comprehensive Plan, the Trust for Public Land Parks Report.